Can AI Cure Cancer? It Already Is.

AI is already transforming cancer care by removing guesswork from diagnosis and treatment decisions. This article explores how Tempus is using advanced analytics, predictive diagnostics, and large-scale clinical data to change how cancer is understood and treated, while also helping shape clearer regulatory pathways for AI-driven diagnostics. As technology and FDA strategy evolve together, the barrier to market access for cancer diagnostic software is lower than ever.

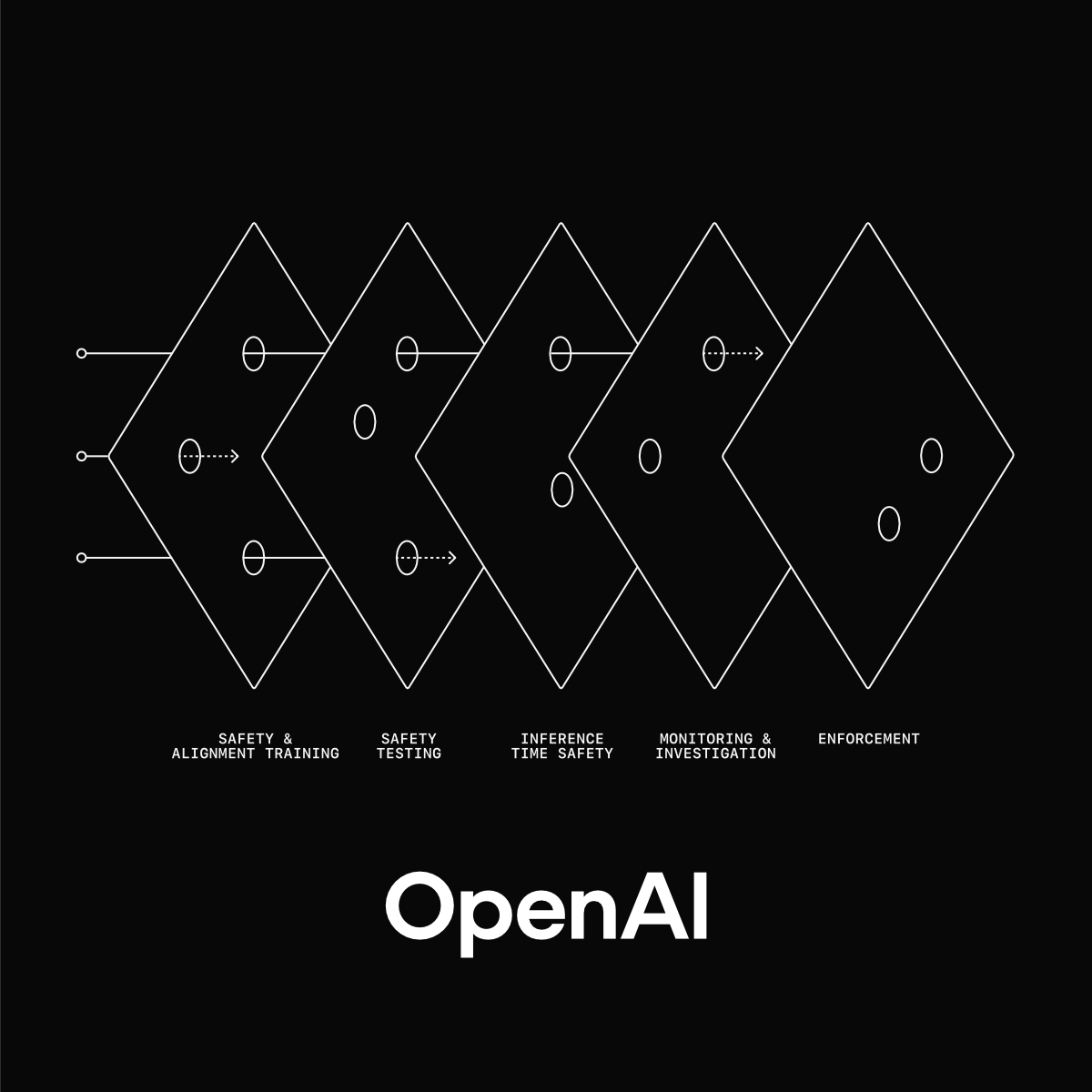

What Clinical AI Can Learn from OpenAI’s Safety Strategy

As clinical AI systems evolve after deployment, traditional reactive quality management is no longer sufficient. This article explores what medical AI can learn from OpenAI’s safety strategy, showing how leading indicators, continuous monitoring, and lifecycle control can help detect risk early and strengthen real-world assurance.

The Preventive Care Gap in the US and a UK App Built to Fill It

Preventive care is one of the biggest unmet needs in the US healthcare system, and remote patient monitoring is emerging as a powerful way to close that gap. This article explores how a UK-based digital health platform like Emerald is already addressing this challenge within the NHS, and what it would take to successfully bring a similar model to the US market. Using Emerald as a case study, it breaks down how thoughtful FDA strategy, from intended use to predicate selection, can turn international traction into a clear and achievable US expansion path.

The lean SaMD regulatory approval starter kit: like an MVP but for documentation

Getting your first SaMD product ready for FDA review doesn’t have to mean months of paperwork, an expensive QMS platform, or a fully mature quality system. What you really need is the regulatory equivalent of an MVP: a lean, strategic collection of ISO 13485–aligned documents that prove your software is safe, controlled, and ready for submission. This guide breaks down the essential “starter kit” every MedTech innovator needs, showing you how to build only the documentation that matters—and nothing that slows you down.

Choosing the Right Predicate Device: The Most Important Step in Your 510(k) Strategy

Before you can prepare a 510(k), you need to choose the predicate device your product will be compared against, and this single decision can determine whether your submission moves quickly or gets pushed into a longer De Novo or PMA pathway. For SaMD and AI-enabled tools, predicate selection shapes your intended use, evidence needs, testing strategy, and how FDA interprets your technology. In this guide, you’ll learn how to evaluate potential predicates, avoid common traps, and choose the device that positions you for the fastest and most successful clearance.

How Intended Use Shapes Your SaMD Classification and FDA Pathway

Before you can choose a regulatory pathway or even draft your first requirements document, you need to define your SaMD’s intended use. This single statement determines your risk classification, evidence expectations, and whether your product qualifies for a fast 510(k), a longer De Novo, or a full PMA. In this guide, you’ll learn how intended use shapes your entire regulatory strategy and how to position your software (especially AI-enabled tools) for the right pathway from the start.

Medical Device Regulation 101: How to Prepare for (and Survive) FDA Approval

If you are building your first medical device or SaMD product, the FDA approval process can feel confusing, expensive, and full of hidden hurdles. This guide breaks down the essentials you need to understand from day one, including how your intended use shapes risk classification, which regulatory pathway your product will follow, why innovation often slows approval instead of speeding it up, and what quality and documentation steps you should put in place early. Start here to get a clear, founder-friendly roadmap through the regulatory landscape and learn how to navigate it with confidence.